Civilisations: Rise and Fall - Everything you need to know about the landmark new four-part series from �鶹�� Arts

Explore the ancient worlds of Rome, Egypt, the Aztecs and Japan... and what led to their fall

The moments when four ancient worlds faced disaster are brought to life in an epic new series exploring Rome, Egypt, the Aztecs and the samurai of Japan. Drawing on the beautiful art and artefacts left behind by these four cultures, now held in the British Museum, the series reveals the human stories at the heart of each crisis.

A �鶹�� Studios production for �鶹�� Two and iPlayer, Civilisations: Rise and Fall begins on 24 November

CB

Introduction from Suzy Klein, Head of �鶹�� Arts & Classical Music TV

“Bringing Civilisations back is a momentous occasion, and a real honour. Civilisation - as it was originally known - first aired in 1969, hosted by Kenneth Clark. This series became a defining piece of television, opening up a world of art and culture to audiences at home - and spectacularly in colour.

“In 2018, Dame Mary Beard, David Olusoga, and Simon Schama took the helm and expanded the series’ scope. They took a global view, looking at the role that art has played in shaping civilisations across the world, and how material culture can serve as a bridge for understanding between different cultures and communities, providing a common language to understand shared human challenges.

“Civilisations: Rise and Fall is the next iteration, building on this important legacy, and bringing a fresh eye to this landmark series and its subject. We take audiences through four major civilisations: Ancient Rome, Cleopatra’s Egypt, the samurai of Japan and the lost world of the Aztecs.

“But this series of Civilisations also has a crucial difference. It comes at a particularly poignant time, as we live through our own period of social and cultural change.

“The series explores not just the rise, but the fall of these four great civilisations and the factors contributed to their decline from prominence, and the roles that pandemic, inequality, migration, climate change, warfare and poor leadership had to play. What lessons can we learn from the art and artefacts that they left behind?”

Episode One - Rome

In 395 AD, the emperor Honorius inherits a vast but fragile empire. For more than 400 years the Roman empire has ruled territory encompassing a multitude of people and languages - but keeping this disparate whole together is a massive challenge, and decisions taken by Honorius’ predecessors have opened up alarming faultlines within the system.

These cracks, which are slowly weakening Rome, are encoded in its artefacts: the Honorius Coin depicts an image of the emperor standing on the body of a barbarian, a Terracotta Theatre Mask reveals deep-seated Roman prejudices towards northern peoples, and a wedding gift made for one of Rome’s elite couples, known as the Projecta Casket, attests to inequality in Roman society, and the wealth of the one percent.

Guided by General Stilicho, Honorius must control a fractured system plagued by rebellion, economic inequality, and a corrupt elite.

The challenge becomes acute in in 410 AD when Rome’s greatest existential crisis in 800 years arrives: the Visigoths, led by Alaric - a Goth leader bent on revenge - besieges and plunders the city, sending shockwaves through the ancient world and marking the beginning of the end for the Western Roman Empire.

Rome Q&A

Q&A contributors:

• David Gwynn, Associate Professor in Ancient and Late Antique History, Royal Holloway, University of London

• Baroness Amos, Master, University College Oxford; Politician and Diplomat

• Richard Hobbs, Senior Curator of Roman Britain & Late Roman Collections at the British Museum

• Shushma Malik, Associate Professor of Classics, University of Cambridge

• Kate Cooper, Professor of History, Royal Holloway, University of London

Other episode contributors: Professor Kristina Sessa, Professor of Ancient History, The Ohio State University, Dr Luke Kemp, Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, University of Cambridge; Peter Heather, Professor of Medieval History, Kings College London; Professor Alice Poletto, Classical Archaeologist.

The art and artefacts that feature in this episode hold clues to why the Roman Empire declined and eventually fell from power. Is there one that you found particularly compelling?

Kate Cooper: The Projecta casket is fascinating because it shows how captivating the Christians found the 'pagan' gods and goddesses. With her glamour and sexiness, the goddess Venus was still part of the cultural landscape after the triumph of Christianity - she was the closest thing a young Roman Christian had to a celebrity or an influencer.

David Gwynn: I would have to choose the Esquiline Treasure hoard. Not simply the Projecta Casket, which is magnificent in its own right, but the entire collection for what it reveals about how life for a certain social class has (and has not) changed over time; the insight it gives into women’s lives (so often obscured in our male-dominated sources); and for the very fact that the collection survived from such a crucial period in history and the enduring mystery of why no one returned to reclaim the treasure after the Sack of Rome.

The Roman Empire under Emperor Honorius was dealing with a number of challenges including mass movement of peoples on their borders - how much does that speak to our own time?

Baroness Amos: The issue of conflict, migration of people and refugee flows is a significant contemporary matter. If a huge number of people end up on your border, it means that something has gone really, really wrong. Even today 100,000 people is a lot of people. In Roman times, they will have been looking at the people camped out, at their own resources and thinking about how to look after people who need to be fed and housed, so that they don't become a problem further down the line.

David Gwynn: The parallels are impossible to ignore. The refugee crisis faced by the modern western world is on a scale even greater than that experienced by the Romans from the 370s onwards, but the fundamental issues are the same. We need to understand why people are moving and reconcile the preservation of existing identities with the advantages of integration. Like the Romans challenged by the arrival of the Goths, and the Goths who admired Roman culture yet fought for independence, we are struggling to find that balance and avoid the conflict which such pressures can bring.

Shushma Malik: Migration and human movement have always been a fundamental part of history. For Rome, that includes movement around the empire as well as across its borders. Well before the Sack of Rome in 410 CE, Romans had been recruiting people into the army from outside of the empire and importing people to work as farmers and agricultural labourers. Romans traded regularly across borders, and migrants who settled in the empire made economic contributions to its infrastructure. The mass movement of peoples that we see in the fourth and fifth centuries was likely for a number of reasons - economic, social, environmental - and certainly shifted power dynamics around the Mediterranean.

But rather than associating human movement with cataclysmic or even apocalyptic events, what the nearly 1000 years of the Roman empire actually teaches us is that migration forms a normative and essential part of political and social structures, and often directly contributes to their success.

One of artefacts we see in the film - the incredible Projecta Casket - speaks to the vast wealth held by the super-rich ‘one percent’ of Roman elites. What role do you think wealth inequality played in the fall of Rome?

Kate Cooper: These objects help us to see is that a world where the rich are seen to be getting richer while the poor get poorer can be dangerously unstable. One of the things that contributed to the Roman empire's decline was a sense that the people of Rome were no longer respected as stakeholders in Rome's achievements.

David Gwynn: Wealth inequality is another issue shared by both the Romans and our modern world and caused tensions for them just as it does for us. However, such inequality had existed in the Roman empire for centuries before the western empire fell and continued to exist in the eastern Roman empire which survived. So this was not a decisive factor in itself, but one that created weaknesses which were then intensified by the wider forces impacting upon the empire, particularly the increasing pressures across the frontiers. It should also be acknowledged that many wealthy Romans survived the western empire’s collapse, with the old aristocracy still influential in the emerging Germanic kingdoms of the Visigoths, Ostrogoths and Franks.

Richard Hobbs: The last decades of the Roman Empire in Western Europe have been dubbed by some as an ‘Age of Decadence’ and objects such as the spectacular Projecta casket are physical evidence of the elites flaunting their wealth at the expense of the citizenry. There are many periods of history when extremes of wealth inequality led to radical social change - think of the French and Russian revolutions - and although we don’t have any direct historical evidence for a popular uprising, it is quite possible that civil unrest (as opposed to external invasions) played a part in bringing down the Empire. So the casket, and the rest of the silver treasure to which it belonged, may well have been buried on the Esquiline Hill in Rome just as much due to fear of it ending up in the hands of ‘barbarians’ as the thousands of poverty-stricken people trying to eke out a living in Rome at this time.

The Roman Empire dominated Europe for 500 years. Do you think its fall holds any lessons for our own future?

David Gwynn: History is the study of humanity, and there is no point in studying the past if we do not try to learn lessons for ourselves and those to come. The Roman Empire’s fall is a reminder that human society constantly changes, and the speed of that change is faster now than ever before. The Romans may have believed their world was secure. We cannot make that mistake. Instead, we all need to consider how we might shape the changes for the better. Mishandling a moment of crisis, as the Romans did when the Goths came to the Danube in 376, can lead to disaster. Yet crisis can also lead to new beginnings and even a new world order.

Episode Two - Egypt

The 3,000-year-old empire of ancient Egypt faces disaster, as war, famine and a toxic dynasty threaten its survival. Will Queen Cleopatra become the last of the pharaohs?

Egypt is the jewel in the crown of ancient history, and by the 1st century BC it has thrived for three millennia led by a single, all-powerful ruler, the Pharaoh.

The natural resources of a land watered by the fertile River Nile have allowed the Egyptians to build a vast and powerful kingdom, stretching from the Mediterranean deep into Africa. Egypt’s wealth has enabled the rise of powerful Pharaohs like Ramses II, whose colossal statue with its cobra headdress symbolises national unity and divine authority. The Pharaohs are not just rulers but considered divine beings, tasked with maintaining cosmic order.

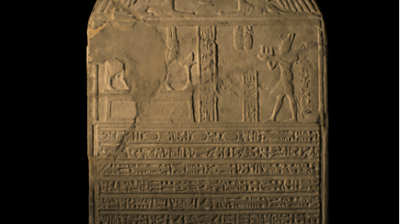

A thousand years after Ramses II a new dynasty rules: the Ptolemies, a toxic royal family whose blood-soaked 200-year-old reign threatens Egypt’s very survival. Their treacherous family rivalries are laid bare in a blank Cartouche Stela, which testifies to the instability of the Ptolemies: pharaohs change so rapidly that stonemasons cease to carve their names on public monuments.

Cleopatra ascends to the throne as Queen of Egypt in 51 BC. As Pharaoh she inherits one of the wealthiest empires on Earth - and a crumbling dynasty plagued by infighting, betrayal and political chaos. Her rule is challenged by her younger brother, Ptolemy XIII, who gains the military backing of the Greek elite. Cleopatra, ever the tactician, seeks an allegiance with mighty Rome and seduces its leader, Julius Caesar, securing her throne once more.

But brother and sister have unleashed dark forces. Civil war erupts in Egypt, culminating in the burning of the city of Alexandria and the destruction of its famed library.

When a massive volcanic eruption disrupts the Nile’s flood cycle, it leads to famine and economic collapse. As faith in Cleopatra’s divine rule wanes, Egyptians turn instead to animal gods like the crocodile god Sobek, mummifying millions of creatures.

Still determined, Cleopatra gives birth to Julius Caesar’s son, Caesarion. She envisages a new Egypto-Roman empire, as declared on the Stela of Caesarion. But Caesar is assassinated before he can declare Caesarion his heir, and his nephew - Octavian - succeeds him in Rome. Cleopatra allies herself with the Roman general Mark Antony and goes to war with Octavian, but their forces are badly defeated at the Battle of Actium and Cleopatra takes her fate into her hands, choosing to die by the fatal bite of a snake than to become a prisoner.

When Caesarion is hunted down by Octavian’s troops and murdered, the Egyptian pharaonic line ends, and Egypt becomes a Roman province. Toxic in-fighting, environmental disaster and violent ambition have led to the collapse of a civilisation that once seemed eternal.

Egypt Q&A

Q&A Contributors:

• Professor Toby Wilkinson, Egyptologist and author; Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge

• Islam Issa, Professor of Public Humanities, Birmingham City University; British-Egyptian historian and author

• Salima Ikram, Distinguished University Professor, Amelia Peabody Chair in Egyptology, American University in Cairo

• Professor Joann Fletcher of the University of York, Lead Local Ambassador for the Egypt Exploration Society and patron of Barnsley Museums & Heritage Trust

• Doctor Aurélia Masson-Berghoff, Curator: Late Period, Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt, Department of Egypt and Sudan, British Museum

• Joseph Manning, William K. And Marilyn M. Simpson Professor of History and Classics, Yale University, Professor, Yale School of the Environment

Other episode contributors: Dr Luke Kemp, Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, University of Cambridge; Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones, Professor of Ancient History, Cardiff University; Alastair Campbell, political strategist.

Cleopatra’s reign was plagued by dynastic infighting and undermined by a “perfect storm”: famine, flood, the shock of volcanic eruption and attack from Rome. Is there anything she could have done differently?

Toby Wilkinson: The question is not why Cleopatra failed, but how she managed to succeed for so long in the face of overwhelming odds. Every other vestige of Alexander the Great’s empire had already been swallowed by Rome. Yet Cleopatra maintained Egypt’s independence for two decades, using all her political skill and personal charm. At home, her swift action saved Egypt from famine. Had she not allied herself with Julius Caesar then Mark Antony, Egypt would surely have been lost earlier.

Salima Ikram: It’s hard to see what solutions that Cleopatra could come up with - a pity that she chose Antony rather than Octavian (not that he was on offer), and that Antony turned out to be less of a general than he should have been. She managed quite well despite all the calamities befalling Egypt and the fact that she herself had to wrest power from her brother, fighting on several fronts, and dealing with the increasing strength of Rome.

Joseph Manning: She had a lot on her plate. More focus on Egypt I would say, many difficult problems - there was the Nile flood weakness, food supply and so on. But she also needed an army.

Islam Issa: Cleopatra inherited a host of tough challenges, including reduced harvests, civil unrest, inflation, and of course Roman interference in Egypt. She actually works quite hard to restore Egypt’s economic and political fortunes and part of that is an attempt to rebalance the power dynamic with Rome. Her alliance with Caesar represented an enormous risk - and I can only try to imagine what was going through her mind when his fires reached Alexandria’s Great Library.

So, one thing she might have done differently - and this might be a rather unexpected answer - is to save some of the writings that were lost at the time. Classical historians put the number of destroyed books between 40,000 and a staggering 700,000; these lost works might even have offered us another version of these events.

The Ptolemies have been described as a toxic dynasty. What lessons can we learn from their infightings and how it affected their governance of Egypt?

Toby Wilkinson: To quote Abraham Lincoln, “a house divided against itself cannot stand”.

Salima Ikram: Geraldo Rivera [journalist and political commentator] would have loved the Ptolemies - so much infighting, scheming, and hatred! Had they been less keen to profit themselves and been less self-indulgent and more sensitive to the needs of the Egyptians and holding strong against the increasing number of ‘world’ powers, they might have been more successful and beloved rulers and taken the lead in world affairs. Who knows, maybe the Romans would never have become the dominant power!

Joann Fletcher: Given how many other ‘toxic dynasties’ the world has had to suffer down the centuries - and indeed still does in some places - we really need to offset such ‘bad press’ with the fact that the Ptolemies were perhaps the greatest patrons of culture the world has ever seen.

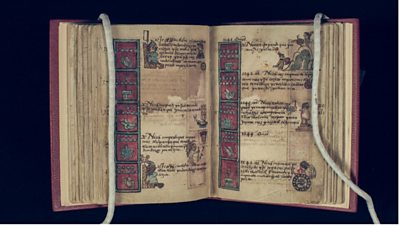

They spent vast fortunes on state-funded research, which made Egypt the intellectual capital of the ancient world for the last three centuries BC. They also rebuilt most of Egypt’s major temples, with those visited by tourists today usually these same Ptolemaic rebuilds. And it's only because the Ptolemies issued their royal proclamations in a bilingual blend of their native Greek language alongside Egyptian script that hieroglyphs could finally be translated in 1822, allowing us to finally start to understand Egypt’s ancient history. So we really do owe the Ptolemies a very great deal.

Joseph Manning: The dynasty was problematic, as all dynastic families are. Sometimes children are on the throne - that was also a major issue of course. Extra added tension because of the intermarriages with the Seleukid dynasty. On the other hand, the Ptolemaic dynasty was the longest lasting dynasty in Egyptian history.

Islam Issa: The Ptolemies were regarded as legitimate rulers of Egypt for a good three centuries. Their influence on Egypt was immense, including monumental projects like the Great Library and the Pharos Lighthouse, which was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. They introduced some successful economic models in Egypt and really understood the meaning of soft power. They did, however, reveal the flaws of dynastic rule: while some Ptolemies were competent leaders, others were unfit to inherit a country as vast as Egypt. But the key lesson from their infighting relates to prioritisation. The national interest should always come before individual ambition. And while foreign relations are important, independent sovereignty must always be maintained.

The Ancient Egyptian artefacts which feature in this episode hold clues to why the Ptolemaic dynasty fell from power. Is there one that you found particularly compelling?

Salima Ikram: The Stela of Ptolemy XII with the blank cartouches is particularly poignant as it speaks to the fact that the carvers were unsure as to who would be in power and who would be paying them for their work - everyone was on tenterhooks as the dynasty was so unstable and there was so much infighting and murder.

Islam Issa: Honestly, every artefact I came across for this episode is fascinating. The crocodile mummy is very striking; it reminds me of how the crocodile god Sobek was one of the earliest deities worshipped in Egypt, associated with military strength and protection. Some sacred crocodiles were kept in temple enclosures where they were fed and venerated. That the Ptolemies promoted Sobek’s worship is telling. Not only were they affirming themselves as Egyptian pharaohs, but they were also projecting their power. I have always been a big fan of Horus and what’s fascinating about this god is his ability to endure no matter who controls Egypt. The figure here resembles a Roman centurion, so in the pursuit of power, even the gods were being transformed.

Aurélia Masson-Berghoff: The Rosetta Stone is famous for unlocking the secret of Egyptian hieroglyphs, but its true story goes far beyond language. The decree carved into it in 196 BC offers a glimpse of a kingdom in crisis. Beneath the lavish praise of the young Pharaoh Ptolemy V lies a tale of rebellion, betrayal, and a dynasty on the edge. The decree was issued during a time of significant external pressure, with the Ptolemies losing their eastern territories to the Seleucids.

Meanwhile, Egypt itself was fracturing. The royal court was consumed by intrigue and murder, while uprisings erupted from north to south. The so-called “Great Revolt” raged for two decades (205–186 BC), as Egyptians even crowned their own pharaoh in defiance of Greek-Macedonian rule.

Archaeology has recently brought this turmoil vividly to life. At Tell Timai in the Delta, traces of fierce battle - mirroring the conflict described in the Rosetta text - reveal burnt ruins, unburied bodies, the defaced image of a deified Ptolemaic queen, evidence of both rebellion and ruthless retaliation. The decree’s promises of tax cuts and amnesties reveal a desperate bid to restore unity and legitimacy.

A century and a half later, Cleopatra VII would face the same impossible struggle: to placate her people, navigate dynastic strife, and fend off foreign powers. The seeds of the Ptolemies’ fall were already written into the Rosetta Stone.

Episode Three - The Aztecs

By the early 1500s, under the strong leadership of Emperor Moctezuma II, the Aztec civilisation has reached its zenith. The jewel in its crown is the beautiful island city of Tenochtitlan, built in the middle of the lake Texcoco.

Aztec society is progressive, with universal education and both men and women fulfilling specific and valued roles. Its formidable military culture draws on the power of apex predators like the eagle and jaguar, represented in the outfits of some of the most elite Aztec warriors.

The ritual practice of human sacrifice helps Moctezuma to rule his empire with absolute authority, terrifying his enemies into submission. This is symbolised by the Sacrificial Knife in the collection of the British Museum, with its turquoise tesserae and eagle motifs.

The empire also relies on a harsh system of taxation imposed on his subjects, the ‘tribute’, which is encoded in a remarkable object from the Aztec world: the Turquoise Skull. Its mosaic covering is of dazzling turquoise, black lignite and red oyster shell, precious materials that Moctezuma demands from the wider Aztec Empire as tribute. Beneath the layer of precious stones is a human skull.

In 1519, the arrival of an avaricious band of Spanish Conquistadors, led by Hernán Cortés, will plunge the Aztec world into chaos, and become one of the most fateful moments in world history- the meeting of the Old and New worlds.

As Cortés and his men reach the mainland, the news of their arrival reaches Moctezuma and he send gifts of gold. For the Aztecs, gold was the preserve of the elites and is not just valuable currency, but a sacred sign of the gods on earth. It is not meant as a welcome but as a display of power, intended to intimidate. This is a catastrophic mistake. The Spanish see it as a submission and it only serves to inspire Cortés to seek out more riches.

Aided by Malintzin, an indigenous slave girl with a gift for languages, Cortés is able to harness local grievances against Moctezuma’s rule and builds an army of more than 6,000 local allies, before heading for the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan.

Within months Cortés takes Moctezuma hostage and chaos soon unfolds in the city. Moctezuma is killed, Cortés and his men flee, leaving behind a devastating trail of disease which will decimate the Aztec capital and weaken any resistance left. Tantalising evidence for a new and mysterious disease may be embedded in the most iconic artefact of the Aztec world: the Turquoise Mask. Designed to be placed on corpses at the time of a funeral, it contains unexpected details. Could the raised turquoise stones represent blisters - marking the arrival of the smallpox virus?

When the Spanish return to besiege the city, they fight the Aztecs to the death. On 13 August 1521, Tenochtitlan surrenders and the Spanish take control of the capital. The Aztec civilisation has fallen: an empire destroyed from both within and from outside.

The Aztecs Q&A

Q&A Contributors

• Dr Amy Fuller, Senior Lecturer in the History of the Americas, School of Social Sciences, Nottingham Trent University

• Devi Sridhar, Professor of Global Health, University of Edinburgh

• Dr Elizabeth Baquedano, F.S.A, UCL Institute of Archaeology

• Dr Jessica A. Fernández de Lara Harada, Post-Doctoral Fellow in Mexican History, at the Faculty of History, University of Oxford.

Other episode contributors: Professor Matthew Restall, Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Colonial Latin American History, Anthropology, [and Women's Gender and Sexuality Studies, Director of Latin American Studies], Penn State, College of the Liberal Arts, Dr Luke Kemp, Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, University of Cambridge; Antony Gormley, Sculptor; Dominic Sandbrook, Historian; Professor Caroline Dodds Pennock, Professor in International History, University of Sheffield; Camilla Townsend, Board of Governors Distinguished Professor of History; Abelardo de la Cruz, Anthropologist.

The role of La Malinche - who became Cortes’ translator, and potentially even his lover - has been debated throughout history. Many have criticised her for what they see as her role in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire. These views have changed over time - how do we view La Malinche, or Malintzin, today?

Amy Fuller: I would say that being labelled as Cortés’ lover is something that was especially prevalent in post-independence literature in Mexico, in order to present her as a scapegoat for the defeat of the Aztecs, and that she is sometimes still presented this way (especially when she is conflated with the legend of La Llorona - the wailing woman).

However, it is starting to be accepted that the nature of her relationship with Cortés may not have been consensual. There was a big age gap and huge power imbalance, and he was notorious for his bad behaviour with women. People are also becoming more accepting of the fact that Malintzin wasn’t actually Aztec and was from a region under Aztec rule (and she had possibly been enslaved by them also) so she had no reason to be loyal to them. Her agency is also questioned - as an enslaved woman, gifted to the conquistadors by the Maya - what choices did she have? Her reputation varies a great deal, but I think the misogynistic view of her as a traitor is starting to change. Or at least, I have hope that this is the case!

Jessica A. Fernández de Lara Harada: I was born in Jiutepec, Morelos, a majority-indigenous small town in the southern central part of Mexico. I cannot tell exactly at what age I began hearing about Malintzin through the pejorative word ‘malinchista’. To be ‘Malinchista’ is an insult commonly used in Mexico to scold anyone who is deemed to prefer foreigner people, cultures and goods, thereby betraying Mexican nationalism rooted in indigenous cultures.

In fact, as we have come to know through serious and critical research and scholarship, Malintzin was a child enslaved from a very early age, first by other indigenous groups and later by the Spaniards, and she became a sexual slave of Hernan Cortes and others. It is clear to us now that Malintzin must have had a noble lineage for she was fluent in various indigenous languages and became an excellent translator from Nahua and Maya to Spanish. Her role as translator was driven either by her own choice or determined by her own set of historical and personal circumstances which might have left her no better option.

How to give agency back to such a woman, an indigenous woman in the conquest of Mexico, to Malintzin, is what we as historians, Mexicans or any other interested people should be most concerned about now. For is it not impressive that given her background, Malintzin was able to conquer our imagination about the past of Mexico and to shape our present understandings and future possibilities in so many meaningful ways?

The clues to why the Aztec Empire fell from power are encoded in its art and artefacts. Is there one piece featured in the film that you found particularly compelling?

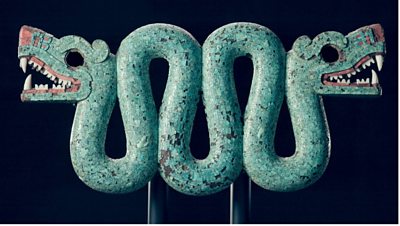

Antony Gormley: The Double Headed Serpent is this absolutely exquisite object that, from the moment you first see it you can never forget, because it imprints itself on your memory. The person that made it must have been aware of the emergent power of this object and been spellbound by it as it was being made.

Jessica A. Fernández de Lara Harada: Our current understanding of the Double Headed Serpent tells us a tale of the Aztec empire as a powerful military, ritualistic and multi-ethnic empire that bolstered its power by controlling vast conquered territories, which provided the raw materials - turquoise stones, shells, gilded cedarwood - used in its creation.

Contrary to what is often assumed, with all its impressive artistry the simple raw materials used in the Double Headed Serpent - marked by the absence of more precious goods such as jade, silver or more gold - can also suggest a second-order gift meant not to invite, but to discourage interest in conquest. By not giving their best gifts to the unusual guests, the Aztecs may have tried to conceal their empire’s true wealth, to avoid the Spaniards’ interest in conquering them.

Elizabeth Baquedano: The Double Headed Serpent. In Nahuatl, the Aztec language, coatl means both snake and twin. The Aztecs observed nature keenly, and anything that seemed unusual, they reproduced faithfully.

Snakes connoted various values, especially fertility and danger. Shedding their skin each year to reveal a new one, they were symbols of the region’s alternating seasons, wet and dry. They also represented danger, rattlesnakes in particular - whose rattle that warns other animals of their bite – so images of serpents often appear with those of warriors. They were made for representing river currents or moving water too, which reminded the Aztecs of flowing blood and, by extension, the processes of the Earth’s fertility. The symbolism extended to cosmology: snakes were thought of as guardians of sacred space.

The double headed serpent is a pectoral. It is covered with turquoise tesserae in the hues of blue that the ancient Mexicans so valued. For them, this snake evoked water, fertility and the sky. The beauty and the skill of the craftsmanship that went into making turquoise mosaics prompted Cortés to include them in his first shipment for presentation to Emperor Charles V.

The fall of the Aztec Empire took just two years and is characterised in the film as “ultimately a story about the arrival of the unexpected”. Do you think its fall holds any lessons for our future?

Devi Sridhar: We need to keep humility for our place in the history of human civilisations. Civilisations can collapse even at the height of their achievements and strength - and some of those factors have nothing to do with something they did ‘wrong’, but just an external force arising, whether it’s smallpox (disease), or drought (major weather changes with climate change), or the instability of leaders in other countries.

Episode Four - Japan

For over 250 years, Japan has thrived under the Tokugawa Shogunate, a regime that maintains peace through a rigid social hierarchy, cultural refinement and strict border control. The emperor is a symbolic figurehead, while the Shogun rules as a virtual dictator, supported by a disciplined samurai class.

Japan’s self-imposed policy of strict border control has fostered a unique and distinctive culture. Cities like Edo (modern Tokyo) flourish with artisans, merchants, and scholars. Art and craftsmanship also reach extraordinary heights, exemplified by the Netsuke - exquisite miniature sculptures which are both functional and artistic. The Samurai sword, or katana, symbolises honour, loyalty, and identity, even as its practical use wanes in peacetime.

But Japan’s peace is fragile. The Industrial Revolution has given Western powers advanced technology and a hunger for empire. In November 1852 American naval commander Commodore Matthew Perry sets sail for Edo Bay with a squadron of steam-powered warships and demands that Japan engage in diplomatic relations with America.

Perry’s ultimatum - sign a treaty or face war - paralyses the Shogun. Japan’s sovereignty, traditions and very way of life are at stake. But the Shogun knows that samurai swords and samurai armour - now largely ceremonial - are no match for the latest western weapons. Perry returns to Japan in 1854 and the Shogun eventually capitulates, signing the first of what become known as ‘the Unequal Treaties’. The Perry Scroll, an incredible 15-metre-long illustrated scroll, painted by a Japanese artist and depicting 16 different scenes, reveals the magnitude and details of this encounter.

Among those most affected is Saigō Takamori, a samurai from the south of the country. He views the treaty as a betrayal of samurai honour and the Shogunate’s failure to protect Japan. In 1868, he becomes part of a rebellion to restore the emperor to power, seeking to control the pace of western influence and preserve Japanese values. It is known as the Meiji Restoration and brings 250 years of rule by the Tokugawa Shogun to an end.

But Saigō’s success is short-lived. Unable to stem the tides of change, the emperor's new government goes further than many expected, transforming Tokyo with railways, newspapers and Western fashion. The samurai class is dismantled, and Saigō’s world begins to vanish. In 1877, he leads the Satsuma Rebellion, a final stand against the new regime. Though defeated, Saigō becomes a national hero, remembered as the Last Samurai. His legacy endures in Japan’s cultural memory, symbolising the tension between tradition and western modernity.

Saigō’s story is a poignant reminder of the cost of cultural upheaval - and the huge transition that Japan faced in the 19th century.

Japan Q&A

Q&A Contributors:

• Dr Satona Suzuki, Senior Lecturer in Japanese and Modern Japanese History, SOAS University of London

• Iszi Lawrence, history presenter and author specialising in historical fiction

• Lesley Downer, author and historian specialising in Japan

• Marcia Yonemoto, Professor, Department of History, University of Colorado Boulder

Other episode contributors: Dr Luke Kemp, Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, University of Cambridge; Mark Ravina, Chair of Japanese Studies, University of Texas at Austin; Dr Christopher Harding, School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Edinburgh University; Dr Rosina Buckland, Curator of the Japanese Collections, British Museum; Max Hastings, War Historian; Edmund de Waal, artist and writer.

Art and craftsmanship reach extraordinary heights in the Tokugawa Shogunate regime, exemplified by objects like the Netsuke miniature sculptures. What does the art tell us about the Japanese culture of the time?

Satona Suzuki: What is striking about Tokugawa art is how functional beauty and refined pleasure could coexist. Objects like netsuke were not made to sit on display, because they were meant to be part of daily life. That sense of physical pleasure, in touching a smooth surface, seeing the design, and using it with pride, speaks volumes about the Japanese aesthetic sensibility of the time.

This is what we call “粋(iki)- sophistication that is understated, sensual, and balanced. It is also an attitude one carries. Everyday objects could become expressions of one’s taste, wit, and restraint. This was a society, especially in the city of Edo, that found elegance not in excess, but in precision. Here, it is important to know just how much was enough.

Iszi Lawrence: Netsuke tell a lot about what was happening in Japan in the mid-19th century. Here you have a practical object used as anchors to attach containers to clothing. Why? Japanese clothing didn't have pockets. Why? Because Japan had isolated itself from Western fashion as well as values.

The Shogunate mandated restraint to keep class distinctions in place. Lavish decorative displays weren't on. You had to be discreet. The subject matter of netsuke is quintessentially Japanese - animals, erotica, everyday scenes and mythology - BUT some are caricatures of foreigners. So, hidden in the clothing of Japanese fashionistas is a countercultural bubbling interest in the outside world. Everyone on the surface upholds tradition but the signs of the change about to come is hidden among the folds of clothing.

Marcia Yonemoto: Across the board Japanese artistic production in this period shows the high level of craftsmanship achieved in many genres, from the netsuke, whose creators came largely from the commoner classes, to art forms like painting and calligraphy, some of which were produced at the behest of the elite classes. This shows how artistic achievement and sophisticated craftsmanship were not monopolized by elites, but were made by and often for commoners, many of whom, especially in urban areas, were wealthier than their samurai overlords.

Lesley Downer: Japanese culture of the time was supremely aesthetic. Under the Tokugawa shoguns Japan enjoyed 250 years of peace, which ushered in an extraordinary renaissance. Artists and artisans created woodblock prints, paintings, netsuke, furnishings, swords, pottery and many other artefacts, all with the highest degree of precision and perfection, like the tiny but perfect netsuke which we see in this film.

Much of this art sprang from the world of the pleasure quarters. There was great wealth, but it was concentrated among the merchant class who were the lowest of the low in samurai eyes because they ‘dirtied their hands with money’. They were forbidden by law to display their wealth. So they invested in tiny, exquisite and hugely expensive items like netsuke that could be easily hidden.

The pleasure quarters which the merchants frequented were largely outside the control of the shogunate. These areas were a looking-glass world where values were turned upside down, where wealth (as opposed to class) was celebrated and a lowly but rich merchant could imagine himself a prince.

Samurai warriors and their incredible armour have become legendary. Who were the real samurai, and what do we learn about them in this film?

Satona Suzuki: It is crucial to contextualise what it means to be a samurai, especially by the 1850s. It is easy to romanticise the image of fearless warriors in armour, but that is only one part of the story. By that time, after 250 years of peace, many samurai had become bureaucrats, scholars, or moral exemplars rather than active warriors. I might add that this “peace” was maintained through rigid social and political control under the Tokugawa shogunate.

What the film reveals is that the samurai were as much about ethics and identity as warfare, and that they were a class endeavouring to maintain dignity and purpose in a changing society. Their legacy is not only martial but also philosophical. It is about discipline, duty, and the search for integrity at all times. Some of those ethics still resonate today.

Iszi Lawrence: The actual role of the samurai changed dramatically over the centuries shifting from court servants to powerful feudal lords to finally becoming quasi-aristocratic bureaucrats. Despite the majority of samurai working in administration they were still fiercely proud of their family origins and connection to the warriors of the past. So even while it was required, many were proud to wear their traditional garments, carry their swords and cut their hair to identify themselves. They were still connected to their past so commissioned and conserved armour like this which they realised they would likely never use.

Marcia Yonemoto: The samurai were warriors, yet they were also scholars, bureaucrats, writers, and artists. Some of the lowest ranking of them were also, especially by the late Tokugawa period, impoverished, poorly or uneducated, and deeply unhappy with their lot in life. Samurai in this way represented the vast political, social, and economic changes that occurred over the course of the Tokugawa period.

Lesley Downer: Samurai were a social class which included both men and women who had a code of behaviour that applied whether you were at war or not. They were entitled to carry two swords (which other classes were not) and to test their sword on a peasant’s neck (though they seldom did so because of the formidable amount of paperwork if they did). They were famous for their courage and death-defying attitude.

The Tokugawa period was a time of peace and martial skills were not needed though many samurai practiced the martial arts. Top level samurai had jobs as government officials or administrators while the lower orders became pen pushers.

When westerners burst in in the mid-19th century young samurai were eager to take up their swords to ‘expel the barbarians’ and their daimyo lords sent them to swordsmanship schools in Edo (now Tokyo). So, as we see in this film, faced with the western threat many samurai became warriors again.

In the 19th century Japan became exposed to the transformational influence of the West whilst it tried to preserve its own traditions. Was Japan destabilised by cultural upheaval, and are there parallels we can draw today?

Satona Suzuki: What happened during the Meiji period was not simply cultural; it was a deliberate project of national survival. Japanese leaders felt threatened by the geopolitical realities of the late 19th century and made a conscious decision to modernise the country at once.

Of course, that process was not without struggle, and they must have felt destabilised by the dismantling of the samurai class, the rapid pace of industrialisation, and the encounter with Western ideas, which created problems and uncertainties. But rather than simply being destabilised, Japan channelled that energy into renewal, transforming itself from a feudal society into a modern nation-state over a short span of time.

As for parallels today, Japan is not facing that kind of existential challenge. It is now a global power, with the world’s fifth-largest economy, and a member of the G7. I would not say Japan is “destabilised” culturally. If anything, it continues to negotiate the balance between tradition and modernity - something it has been doing quite successfully for over 150 years.

Iszi Lawrence: AI technology frightens us. It may destroy our artisans and craftsmen. It threatens to change everything from how we do our jobs to how our society and government is structured. We ignore it and the military technology that develops alongside it, at our peril. Anyone clinging to the old ways may well regret it, given what happened to the brave samurai who dared to make their last stand. What Japan shows us is that while change is inevitable it is also adaptable. Japanese culture didn't end in the 19th century; it grew into something just as complicated and unique. Its story is one we can all learn from.

Marcia Yonemoto: Certainly the changes of the 19th century caused great upheaval for many Japanese, especially literate elites and urban dwellers. But for many, especially in rural areas (the majority of the population) life went on as before. Even in the late 19th century, the majority of Japanese lived in the same type of houses, ate the same foods, and engaged in the same occupations as they did in generations past, during the Tokugawa period. In many ways, the continuities with the past enabled the assimilation of new ideas (integrated with/parallel to old ideas, e.g. time-orientation in industrial work which dovetailed well with Japanese agricultural work regimes) and rapid growth of new technologies (with roots in old practices—see, e.g., role of rural women in textile industry).

Lesley Downer: Rather than being destabilised by cultural upheaval, Japan was energised by it. The Japan that westerners intruded upon was a literate, articulate and highly sophisticated society whose leaders knew far more about the west than the west knew about them. Japan’s civilisation didn’t ‘fall’. The arrival of westerners sparked an upheaval that had been brewing for centuries and enabled the ancient enemies of the shoguns to bring about regime change in a brief civil war. Even with a new government in place the Japanese were able to maintain continuity by retaining the emperor as the lynch pin of the whole system.

The idealistic young revolutionaries who took over after the fall of the shogunate deliberately shaped their new western-facing society, in much the same way that the founding fathers shaped America. Far from being destabilised, the Japanese were keen to explore the new culture without giving up their own. They eagerly adopted western clothes, dancing, food, literature and music. They also wanted to find out what gave these foreigners their power.

Leading members of the new government went on a fact-finding mission around America and Europe to learn the secrets of western industrialisation at first hand and cherry picked the western ideas and social forms they wanted to adopt, modelling their army on Prussia and their navy on Britain and developing western-style law courts, newspapers and engineering.

To this day Japan is a supreme example of a society that has taken on western ways as tailored to their own needs and demands, while nurturing and celebrating their traditional culture. In fact, many elements of Japanese culture are admired and practised in the west - Zen, flower arrangement, tea ceremony and martial arts for a start.

Suzy Klein in conversation with Dr Luke Kemp

Suzy Klein in conversation with series contributor Dr Luke Kemp, Research Associate at the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at the University of Cambridge

Suzy Klein: Luke, you feature in all four episodes across the series. Your role for me is very much about the connective tissue, the larger sense about what the great forces of history are and how those patterns repeat. How much do you see that in your world looking at civilisations across the world?

Dr Luke Kemp: In this, you see there’s not a single silver bullet bringing down a great civilisation. Rather, it's a maelstrom of different factors. In the study of risk, we often talk about risk being imposed of a hazard - the thing that deals damage; vulnerability - essentially why you're weak to that damage; and your exposure and your response. And across all the case studies, we see similar ones cropping up every single time: climate change, for instance, invaders, disease. But also things like inequality, rebellion and poor leadership. And interestingly the second commonality is that we often see the vulnerability as more important than the hazards.

I think we’re familiar with seeing the Aztec Empire as being a collapse in front of this unstoppable force of Conquistadors - Guns, Germs and Steel*. But when you actually look at it, Cortez was almost defeated when he arrived. Thereafter when he eventually takes over, he does it at the hands of a 100,000 strong army - the vast majority… are indigenous, and interestingly the ones who rebelled were from provinces the most heavily extracted from in the Aztec Empire.

Suzy Klein: Finally, if there’s one golden lesson from history - I know you’ve said things don’t collapse, there’s never just one cause - what should we be aware of, what is the lesson?

Dr Luke Kemp: I certainly don’t speak for all of the experts in the series, but from my research, it’s that inequality is the key driver behind most societal collapse across world history and is still relevant today.

*Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies by Jared Diamond, first published 1997

Suzy Klein in conversation with Alexander Leith

Suzy Klein in conversation with Alexander Leith, Executive Producer at �鶹�� Studios

Suzy Klein: We talked about what Civilisations looks like in 2025. Can you unpack very briefly some of the layers and the bits of storytelling kit you were trying to balance and play with?

Alexander Leith: There are points of continuity and points of divergence with the previous two series, the most obvious divergence being is there is no presenter. We wanted to use a range of expert contributors - historians, academics, curators from the British Museum, but also artists and writers and novelists and cultural commentators and politicians, all who bring different perspectives, I think.

Clearly it’s an Art series and the collaboration with the British Museum has been a key aspect; the British Museum has been fabulous, their Care & Collections teams gave us access in the most brilliant way and allowed us to film these remarkable artefacts in the kind of detail I’m sure Kenneth Clark would have been very approving of.

I think the biggest challenge that we had and another point of divergence from the previous two series are the drama visualisations - and they were a huge challenge. We had to build four of the most difficult worlds in drama. Tim mentioned in his speech that the original Civilisation was in some respects about showcasing the use of colour television on �鶹�� Two. We also adopted new technology.

We worked out the only way we could do this is by using what’s called virtual production, which is it's actually how they shot big-budget TV series like The Mandalorian, where you build the interior sets and locations as 3D simulations/models in computer graphics, using software like Unreal Engine, and you create a 3D model, which you then put up on a vast LED screen in a studio, and you film against that.

Suzy Klein: We think this may be the first time that all the drama has been shot using Virtual Production in a Factual series. We were talking about carrying on that legacy as you said, of technological innovation in a very different way from what David Attenborough and Kenneth Clark were doing, but continuing to push forward with what arts and factual programmes can look like.

Follow for more

Latest from the Media Centre

All newsSearch by Tag:

- Tagged with Latest News Latest News

- Tagged with Media Pack Media Pack

- Tagged with �鶹�� Arts �鶹�� Arts